One of the great joys of travelling is that time runs on a slower track. We’ve been here two days and already it feels like I’ve experienced enough to fill a week.

It was another sunny, perfect day and after breakfast I waited in the park for S & P, watching tourists fend off a wizened old Turkish man selling cheap fezzes. Though treated like a pest, he still managed to look grand in his own well-worn, dark red fez.

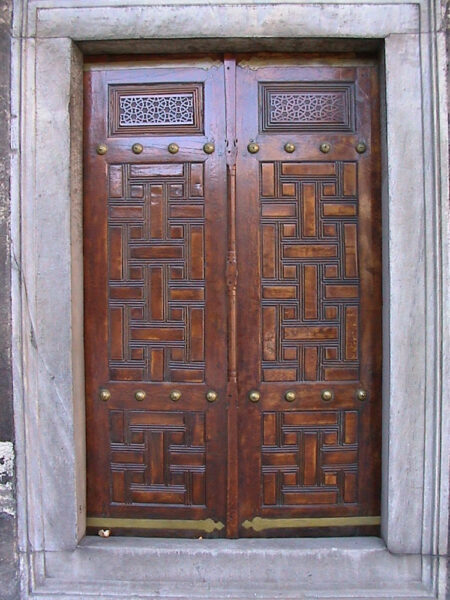

S & P arrived and the three of us strolled over to the Blue Mosque, the gorgeous mosque with its sky-piercing minarets that dominates the view from my hotel terrace. It was built by Sultan Ahmet I (1603-17) who, I will take a wild guess and say, also gave his name to this part of the city – Sultanahmet. We took off our shoes, put them in the plastic bags provided and entered the cool, peaceful, lofty space. Four massive pillars held up the dome high overhead. Our feet padded over soft new carpet. The cavernous interior was brilliantly rendered intimate and personal by a very low lighting rig which hung from scores of wires from the ceiling. As I’ve thought before, if you have to worship, a mosque seems a far more beautiful place to do it in than a Christian church where everything, from the images of a tortured Christ to the hard wooden pews and cold monolithic stonework, seems to be about suffering rather than beauty.

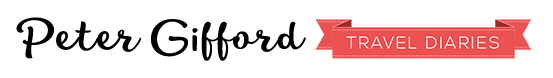

Next we walked through Sultanahmet Park and across to the imposing Aya Sofya, the architectural symbol of Istanbul. After a short queue for a ticket we entered the grounds, past huge exterior buttresses to the Outer Narthex, a stone-clad corridor running left and right from the entrance. Huge doors of bronze linked this with the Inner Narthex, roofed by beautiful gold mosaics. Then into the main chamber; the first impression that of disappointment upon seeing a mass of scaffolding in the centre extending to the roof, but then wonder at the immensity of the space, the height of the dome (almost 200 feet) and the palpable atmosphere of antiquity.

Next we walked through Sultanahmet Park and across to the imposing Aya Sofya, the architectural symbol of Istanbul. After a short queue for a ticket we entered the grounds, past huge exterior buttresses to the Outer Narthex, a stone-clad corridor running left and right from the entrance. Huge doors of bronze linked this with the Inner Narthex, roofed by beautiful gold mosaics. Then into the main chamber; the first impression that of disappointment upon seeing a mass of scaffolding in the centre extending to the roof, but then wonder at the immensity of the space, the height of the dome (almost 200 feet) and the palpable atmosphere of antiquity.

Aya Sofya, The Church of the Divine Wisdom, was completed in AD 537 by the Emperor Justinian, became a mosque when Constantinople was conquered in 1453, and finally declared a museum in 1935. The faiths seem to live together comfortably, as huge medallions with Arabic text on them, high up in the corners, co-exist with a mosaic of Mary and the Christ child on the ceiling above the mihrab.

Restoration work has been in progress since 1992 so the scaffolding isn’t a recent eyesore. Continual repairs since the dome first collapsed in AD 559 must prove a nightmare for the restorationists, who must sort out and repair the different methods and vast quality variation of 1,500 years of renovators.

After a brief visit to our hotels we were catching the efficient tram service to the shore near Galata Bridge, and for the first time we plunged into the crowds of a typical sunny day in Istanbul. The thousands of people buying and selling, hawking their goods in loud voices, the smell of corn on the cob cooking, the acrid whiff of the sewers, scores of fishermen lining the bridge and the wharves, touts trying to sell us boat tours – wonderful chaos.

We walked across the Golden Horn over the Galata Bridge to the opposite shore, and finally gave in to a persistent tout who led us to a nice little resturant where on the second level we had a good view of the water. There we had a lunch of kepap, followed by too much baclava. S asked for Turkish delight and the waiter ran off next door to return with a box-full.

After a leisurely lunch we returned to the southern shore but had missed the last official boat for a ride up the Bosphorus, so we visited the nearby New Mosque (at 400 years of age …) and then plunged into the busy market streets in the general direction of the Suleymaniye Camii, Istanbul’s largest mosque. The narrow streets were packed with stalls with a million things for sale—nuts, fruit, henna, clothes, tools, plastic toys …

Eventually we found the huge mosque and sat down in the shade of a tree in the garden to recuperate for a while. Suleyman I (1520-66) built this grandest of mosques between 1550 and 1557. Inside it was huge and tranquil. In the vast carpeted expanse only two young men, standing close together, were performing their prayers. Little kids weaving amongst the tourists asked to be photographed; I had a group of them fascinated by my video camera, and they all stood together in a little pack and waved and smiled as I filmed them.

We strolled the grounds and looked at the cemetery with its strange white columnular tombstones topped by turbans and fezzes of stone, then relaxed, exhausted, in a beautiful cafe nearby in a garden sunk below the level of the road. Eventually we weaved our way back through market streets to the tramline and thence to our hotels for a rest.

I went up to the terrace and ended up playing three games of checkers with V, the Moldolvian waiter. He had very little English and my Turkish is up to three words, but I managed to discover he was 33, had a wife and two kids (8 and 6 years of age), had been in Turkey three years and working at the hotel one year. He beat me resoundingly at checkers of course, but we’ll see about that tomorrow!

About 8pm S & P joined me on the terrace. P and I drank the ouzo-like spirit raki with water in narrow glasses. After a while we walked down to the Hippodrome and found an outside cafe, packed with locals clapping and singing to a little band playing Turkish favourites. Inside a group of men were glued to a game on a TV set, occasionally jumping up to cheer when a goal was scored. After kepap P retired early, exhausted, but S and I stayed for a while to talk, drink Cokes (no alcohol in the restaurant) and watch the locals.